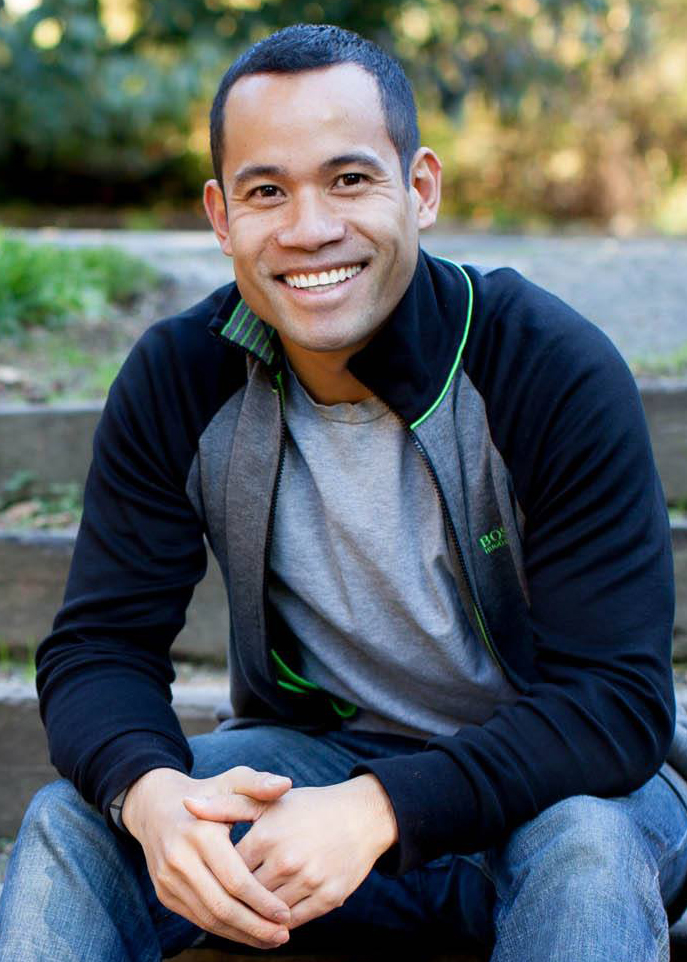

Ken Griffey Jr – August 27, 2008

The Kid.

Baseball legend. Seattle’s defining superstar. Generational talent. All of these terms are routinely used to describe Ken Griffey Jr, one of the greatest sports players of the ’90s. For baseball aficionados, watching Griffey play baseball is akin to listening to Montserrat Caballé sing Ave Maria. But why is this so? And more importantly, why should theatre artists care?

Sure, there were the layout game-saving catches. The singles he turned into triples with speed, guile, and vision. The bullet-like, perfectly timed throws from across the field. More than all this, though, it was the swing.

In an era drunk on steroids and raw power, of McGwire and Sosa hitting 60, Griffey was right there, keeping pace alongside them. The fluidity of that bat’s passing through the strike zone could just as easily turn a low and outside two-seamer into a home run as turn a high change-up into a line-drive single. Griffey had a swing that Bobby Valentine (one of the most infamously irascible coaches in history) famously called “perfect” (Stone). Jay Buhner, his teammate with the Mariners, said Griffey would “…call his shots all the friggin’ time. We’d all shake our heads” (Stone).

That swing was magic, more than just effective; it was beautiful.

Kant argues that our judgment of beauty emerging from an object of perception – or in this case an action “ . . . arises on the achievement of a purpose, or at least the recognition of a purposiveness” (Burnham). For Kant, purpose “is the concept according to which it was made” (Burnham). Purposiveness however has an “intrinsic purpose” whereby “a thing embodies its own purpose” (Burnham). There is a particular and mischievous delight in thinking that because the “universality and necessity” of artistic judgments “are in fact a product of features of the human mind” (Burnham), we could just as easily apply our idea of beauty to actions as something like Kant’s sunset or a painting by J.M.W. Turner.

Griffey’s swing didn’t dazzle Bobby Valentine because it was so effective. In fact, I’m sure it would have been the opposite when he coached for the Rangers. Griffey’s swing stood out since there is “pleasure in something because we judge it beautiful, rather than judging it beautiful because we find it pleasurable” (Burnham).

The act of hitting a baseball is a functional movement. It serves a very real world purpose. While this feat can be described as impressive on its own, there are all sorts of examples of other people (Nelson Cruz) hitting balls very far without the action’s being particularly beautiful. So why is Griffey’s swing so beautiful? Bobby Valentine again: “Once you start your swing, people talk about transferring your weight. I always thought his transfer was impeccable, the way he was able to stride, and have a good stride, and yet stop his weight as he was going forward so he could transfer all that weight to his front foot, get off his back foot, and stay balanced as he translated all that energy to the bat” (Stone). All of this boils down to being able to do something extremely well with style, a little bit of “extra” that adds something not essential, yet not extraneous to the basic action. “Griffey got into the box, and it almost looked like he was dancing” (Stone).

I remember going to see Pina Bausch’s final piece of choreography at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2010 entitled “ . . . como el musguito en la piedra, ay si, si, si …” and being dazzled by the dancers’ simply walking around the stage. It was just walking. There wasn’t even a particular aberration of the movement, but it mutated from sensual to unnerving in an instant, yet never deviated from the essential action of needing to carry each individual dancer’s body across the stage. Bausch’s dancers floated with, like Griffey’s swing, “ . . . this dance of balance that performers reveal in fundamental principles common to all scenic forms” (Barba). The shift of balance is not done simply for itself. It is a functional movement—a functional movement that is nevertheless enacted with a certain style and specificity, a little something extra that transforms it from basic action into beautiful action.

Theatre is constantly faced with a tension between establishing something real, while simultaneously establishing something beautiful. In day-to-day existence, people strive to “ . . . follow the principle of minimum effort, that is, obtaining a maximum result with a minimum expenditure of energy” (Barba). In performance, the performer is faced with the particular problem of making actions “ . . . which do not respect the habitual conditionings of the use of the body” (Barba). The audience wants to see something real, as in action that accomplishes something verifiable, and yet is also something that has a little flair. Flair that isn’t added on or layered but that is central to the action. There is a subtle shift of focus by the actor not only from the effective and skilled execution of the action but towards something greater.

Whatever that greater thing is can be left open, maybe even unknown explicitly to person performing the action. Étienne Decroux, the father of corporeal mime, is described as having a “ . . . lion inside him and his technique kept it at bay” (Barba). When we see truly incredible performance on the scale of Griffey’s willfully distributing balls about the field, or Bausch’s dancers gliding across a stage, we see not just the action itself, but what they are pointing towards: the lion in the quote about Decroux.

Such mastery over technique hints at a different aesthetic experience that is called by Kant the Sublime, which “names experiences like violent storms or huge buildings which seem to overwhelm us; that is, we feel we ‘cannot get our head around them’ ” (Burnham). People find these actions awe-inspiring because they relate beyond the actions themselves towards a rational idea that is absolute in some way: “Extra-daily techniques . . . lead to information” (Barba). True expression of genius can be called “beautiful, but in addition is an expression of the state of mind which is generated by an aesthetic idea” (Burnham). Information that gets communicated from functional movement at the scale of Griffey seems to relate less to a quotidian idea and more towards something that has a capital letter in front of it.

For years that bat gliding through the strike zone enraptured millions. But it wasn’t just how good Griffey was at swinging that bat; it was the way that he was good at it that made it so special. The real trick is to be able to do that on stage when the performer only has to pick up a teacup.

Works Cited

Barba, Eugenio. The Paper Canoe: A Guide to Theatre Anthropology. Trans. Richard Fowler. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Burnham, Douglas. “Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2016.

Stone, Larry. “For Hall of Fame-bound Ken Griffey Jr., it all started with the swing.” 5.1.2016. Seattle Times.

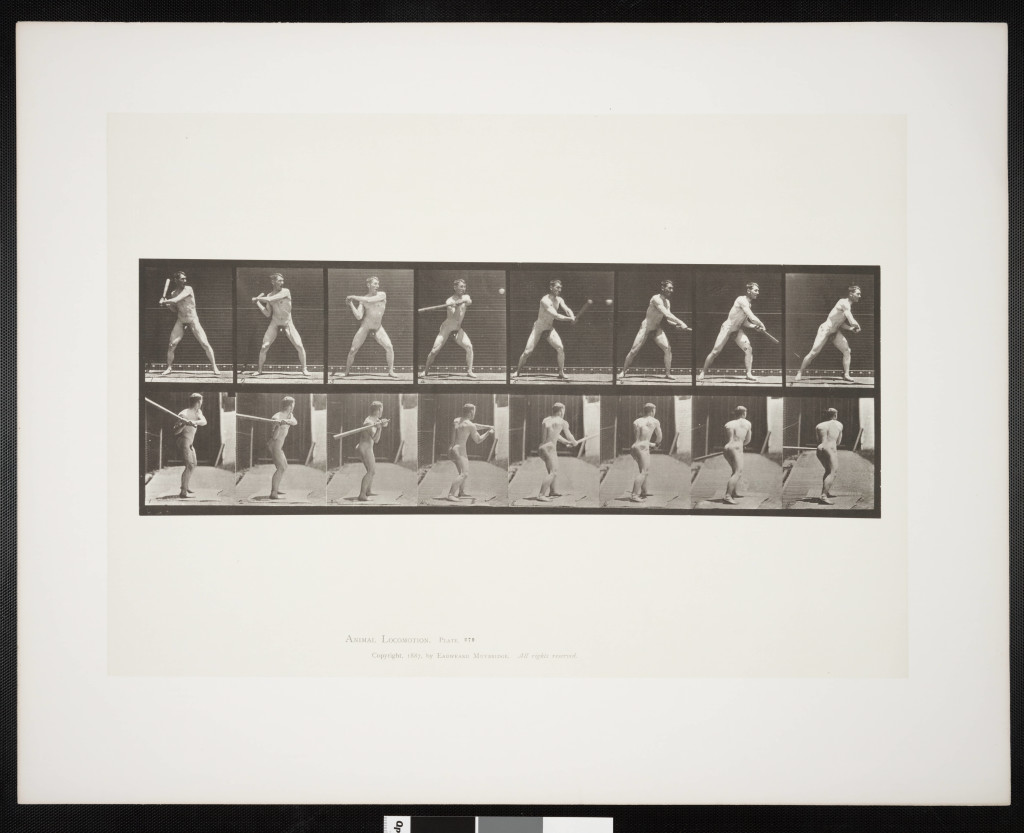

Eadweard Muybridge. Animal locomotion: an electro-photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements. 1872-1885 / published under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania. Plates. The plates printed by the Photo-Gravure Company. Philadelphia, 1887 / USC Digital Library, 2010.